first appearance: Foredrag med Kenjiro Okazaki og You Nakai at Anthroposophical Society in Norway (Oslo),11.Sep.2017

The Network of Invisible Things

Many Yokai’s(Sprites)Inside Oneself

It is a great honor for me to be able to give this talk at Anthroposophical Society today. I thank you for the opportunity. I am basically an artist, though in parallel to my artistic activities, I have thought and written about things around art so I’m also regarded often as a critic. But my concern is art, and my interest in culture in general is only an extension of this primary focus.

However, if one attempted to understand the shifts that occurred in modern art, its background obviously concerns culture in general. When a big change occurs in the fine arts, it is always the case that this change cannot be comprehended as a development that pertains strictly to art. For instance, the emergence of abstract art represents one of the biggest shifts in art in the Twentieth Century. But the shift of cognition underlying abstract art had already taken place in the nineteenth century. Abstract art corresponds to the core problematics of what is broadly called “Modernism.”

Based on these ideas, I curated an exhibition from April to June this year, at the Toyota Municipal Museum of Art, which reconsidered the emergence and development of Abstract Art.〝Abstract-Art-As-Impact〟(抽象の力) . A part of what I thought in connection to this exhibition is written in the text I’ve handed out so I’d be grateful if you could read it.

The exhibition was organized based on the thesis that the premise for the emergence of abstract art lay in the doubt towards grasping something through its visual representation. This suspicion towards the visible, so to speak, has three aspects:

1. is the awareness that what is represented is reduced to a method pertaining to a particular culture; 2. is the awareness of a radical increase in observable data brought about by shifts in technology; and 3. is about the transformation or evolution of scientific cognition. These all reflect structural shifts in culture that occurred in modernity.

The late nineteenth century development in art from Realism to Impressionism corresponded precisely to such shifts of cognition. This was already apparent in the works of Turner or Constable. The poet Rimbaud and Cezanne, who was the same age as Rimbaud, gave a name to the experience of intensity that goes beyond the senses to grasp an object in a direct manner: “sensation.” As is well known, correspondence was a phenomenon where individual senses resonated together despite their differences, forming a singular, holistic experience. The search for this immediate experience was already of interest to artists around the world by the end of the nineteenth century. The logical basis of abstract art is located here.

However, in art history, the common understanding is that abstract art first emerged between 1910 and 1915 when Cubism inherited preceding, primordial attempts of abstraction. But this narrative merely follows the necessity of standard art history, which aims to connect abstract art to the established canon of modern art centering around artists such as Picasso or Matisse. This is why people like Kandinsky, Malevich or Delaunay, who were considered as originating abstraction, have always been measured and justified in relation to the influence of Cubism or Fauvism.

However, if one only switched the focus from the official context of Western Art centering in Paris, to activities on the periphery, it becomes apparent that many abstract art works had already been created without going through Cubism or Fauvism.

As if often mentioned, if Modernism implies a detachment and separation from cultural tradition, and if this detachment is triggered by a revolution in production technology and accompanying increase in the amount of production, in addition to the sudden expansion of trade networks, the principal examples of Modernism should come from the periphery of existent culture rather than its center.

The background for the emergence of abstract art, broadly speaking, can be analyzed through the following five conditions:

The first condition is that abstract art did not originate in countries like France and Germany where abstraction appeared after Cubism, but in Peripheral regions such as Eastern Europe, Scandinavia, or ASIA like Japan. It was obvious that the traditional Western realism appeared as an authoritative and ritualistic convention, an academic exercise that only follow preexisting norms.

The second is that abstraction, at its origin, was influenced by shifts in scientific cognition—especially Natural Science.

The third condition is the influence of production process in Applied Art which had been deemed peripheral in the traditional categorization of art. In William Morris’ words, Applied Art was an accessorial ‘Minor Art’ compared to the so-called Major Arts. In the process of making Applied Art, the individual artisans become absorbed in individual tasks without visually grasping the entirety of the product. Nevertheless, the end product shows a marvelous order and coherency. There is thus a sense of order that does not take recourse to vision.

The fourth condition is the influence of New methodologies of child education, most exemplified by the work of Friedrich Froebel. The distinct character of Froebel’s pedagogical toys, which were called “Gifts,” was that when manipulated and moved by children, a new shape that cannot be reduced to individual appearances of the object is formed. A sphere and a cube reveal a similar geometric nature despite the differences in how they look. The children learn to grasp this abstract nature in a concrete manner.

The fifth condition is related to all the above, but concerns the grasp of Bodily movement. Athletes and dancers cannot see themselves, but always grasp their own movement in a synthetic manner. Although this is not a visual image, it is still an image of sorts.

As is obvious from conditions 3 and 4, research has revealed that many pioneers of abstract expression were female artists. : for instance, Hilma Af Klint, Sophie Taueber-Arp, Sonia Drauney, Katazina Cobro, or Barbara Hepworth.

In the social situation of the times, female artists were alienated from the work of creating representative imagery of society or nation. This was a work assigned to major artists, so the female artists had no choice but to learn and engage in the Applied Arts. Moreover, as Froebel himself envisioned, it was considered a woman’s job to stay by the side of children and educate them. In addition, the Natural Sciences which were not yet considered as practicaldiscipline , were open to research by many amateur scientists which included women.Sciences which were not yet considered as practicaldiscipline , were open to research by many amateur scientists which included women.

In this sense, the emergence of Hilma Af Klint, who has been finally acknowledged as the first abstract artist in the world in the recent years, was not an accident. Above all, Klint was well versed in the Natural Sciences, and I suspect she was also interested in child education.  Ellen Key who wrote the famous book, “The Century of Children” was a contemporary of Klint, and active in the same city of Stockholm, so it wouldn’t be a fetch to think that the two knew each other. Hilma’s involvement in séances─spiritualism. also should not be thought as a heretic detour in relation to the situation of then-cutting-edge science. For the inquiry into the soul and spirit was considered equal to the research of electricity, heredity or spatio-temporal structure since these all shared the same scientific aim of exploring the invisible.

Ellen Key who wrote the famous book, “The Century of Children” was a contemporary of Klint, and active in the same city of Stockholm, so it wouldn’t be a fetch to think that the two knew each other. Hilma’s involvement in séances─spiritualism. also should not be thought as a heretic detour in relation to the situation of then-cutting-edge science. For the inquiry into the soul and spirit was considered equal to the research of electricity, heredity or spatio-temporal structure since these all shared the same scientific aim of exploring the invisible.

A similar cultural background also existed in Japan. As a county which rushed its way to become a new modern nation, even before learning about Western traditional culture, Japan imported the most advanced infrastructure of the day including industry and culture. Because Japan came in late into the game, it tried to incorporate the most advanced production technology and establishment, which included Froebel’s child education, the Natural Sciences, and also craft (the latter genre was expected to bring forth the only products of art that Japan could export).

Froebel education was introduced in the 1870s, during the Meiji era which immediately followed the opening up of the country. Froebel’s writings exerted a wide influence on Japanese novelists and artists from around the early 1900s. As a result, many artists created literary works and picture books for and about children.

As is known, Froebel’s child education system also inherited the tradition of Gnosticism. In his view, all objects had emotion. All the innumerable and individualized objects that fill up the world—all the things that are different from one another—have an emotion that drives them to connect mutually and endeavor to become one. Wisdom is backed up by the workings of this emotion.

The act of understanding an object concerns the collaboration between that object and oneself, or one’s work. Such philosophy gained popularity among artists who were involved in child education. Among these artists, Koshiro Onchi created a print considered to be in Japan in 1915.

Kōshirō Onchi “Lyric: Bleesing for Effort (Tsukuhae VI) ” 1915

What is significant is that the image shown as the finalized work of print does not exist as such in any of the numerous block layers used in the process of making it.

In other words, the final image only appeared when the layers were superimposed—just like how Froebel taught that cylinders and spheres only appeared when the block toys were turned around. Onchi was interested not so much in the nature of prints as reproductive technology, but rather in the event of creating a single printout of many wood blocks. This was an emergence of something that did not exist.

Muneyoshi Yanagi, who belonged to the same cultural circle as Onchi (which centered around the magazine Shirakaba), started his career as a researcher of William Blake, but later became the leader of the craft movement known as Mingei. This movement proved to be extremely influential: for instance, the world-famous brand Muji—which in Japanese means without a mark, or in other words, generic—is considered as following the path first opened up by Mingei.

However, Yanagi himself was astounded by the anonymous craftsmen creating one sacred object after another, while saying dirty jokes to each other. These people were not concerned about envisioning the final result or grasping the entire picture of what they were doing; instead they comprehended the totality of the work through their bodies. Yanagi saw this as a literal embodiment of the teachings of the Nen-Butsu sect of Buddhism which claimed that bad people are the ones who must be saved most. According to this sect, what is good is the very act of reciting a chant, and whether the person chanting is good or bad does not make an essential difference. The capacity to be absorbed in the act is deemed more essential than social status. Yanagi regarded the pottery made by the potter, or the pattern created by pouring glaze in it as being chants themselves.

Goodness only exists in the process through which pottery is created, and people can only take part in this process. What is interesting is that Yanagi, in the transition from his research on Blake to the activities of Mingei, studied science, with a particular focus on the then-recent research of spirituality. He considered this direction to be the future of science. What needs to be understood, is that within these scientific inquiries, the status of spirit had been transformed. A spirit is not something that accompanies individualized and socialized consciousness. Rather, it pertains to a network open to other things and exterior beings that consciousness cannot grasp. Humans are themselves such open networks, and what moves people and inspire ideas is this relationship and involvement to what lies outside consciousness. One cannot fully comprehend one’s own spirit which is exposed to the exterior and influenced from it.

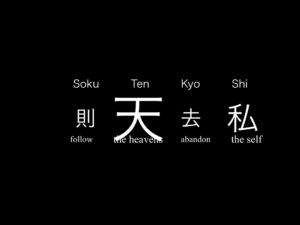

I’d like to briefly revisit a topic I talked about at the panel discussion at the Modern Art Museum two days ago. This concerns the statistical cognition of the novelist Soseki Natsume. Through deep introspection, Soseki discovered that the basis of consciousness is formed by what lies outside itself. Although we may feel we are thinking on our own, Soseki’s insight was that the exterior environment is what makes us think. As I discussed the other day, Soseki addressed this realization using the word “Soku Ten Kyo Shi. What we believe to be our own intention, is actually a thought that emerges as a result of being influenced by something without even knowing so. This something can be one’s own intestines or body condition, but this condition is itself incorporated in the relationship to others, a multi-folded network of influences coming from the exterior environment. In this way, the inner environment is connected to the exterior environment.

What we believe to be our own intention, is actually a thought that emerges as a result of being influenced by something without even knowing so. This something can be one’s own intestines or body condition, but this condition is itself incorporated in the relationship to others, a multi-folded network of influences coming from the exterior environment. In this way, the inner environment is connected to the exterior environment.

We know that Soseki read books on psychology such as William James, although we do not know whether he had read Freud. However, the concept of “Ten” included in his notion of “Sokuten Kyoshi,” is very similar to the notion of “Es (Id)” that Freud explored in his late years. My consciousness is only a small part of the entangled potentiality of the Id, which arises to the surface without knowing where it came from.

Kunio Yanagida, known to have built the basis of ethnography in Japan, was about 9 years younger than Soseki. Like Soseki, Yanagida was a significant scholar who did important work that became a platform for modern Japanese culture to establish itself. The origin of his work was also rooted in the suspicion that the self-consciousness formed in modern society is actually fragile and extremely precarious.

What interested Yanagida was not literature but stories transmitted orally. That is to say hearsay that spread among people like rumors, immersing in and influencing people’s minds.

These stories, which are utterly ambiguous concerning their veracity, gradually accommodate themselves into a certain type of narrative. Such narrative type serves as the format of thought for understanding phenomena, thus regulating how people think. Yanagida’s methodology was in this way similar to Structuralism that would emerge later. Even when modern, rational consciousness seems to dominate everything, these oral cultures, as well as the culture of everyday including gestures and so on, constrain people’s mind as a format of thought without being acknowledged as such.

“Tono Monogatari,” Yanagida’s seminal work from his early years, collected orally transmitted stories from a certain region in the Tohoku area of Japan. The epigraph of the book reads as follows:

I Dedicate This Book to the People Living Abroad

The implication here is that this book would encourage Japanese people feeling alienated abroad. But why? In the preface following the epigraph, we find the following sentence which condenses the intention of the book.

I hope you talk about this and shock the foreigners

Even when Japan became, on the surface, international and modern, a large part of our own minds and bodies remain governed by unknown flows of thought that cannot be well-articulated via language. These thoughts had real powers, sufficiently absurd and at times cruel, which could subvert the flattened consciousness of modernity.

Like Yanagi, Yanagida was influenced by spiritualism at the start of his career. He was interested in how superstitions concerning things we cannot understand rationally, including the world after death, spirits, and Yokai, remained at the core of narrative in oral cultures. Yanagida differentiated Yurei = Ghosts and Yokai =spirits in the following manner:

Yurei = Ghosts haunt people─an individual,

Yokai’s haunt places.

That Yurei =Ghosts haunt people indicates that they are some sort of shadow of self-consciousness —a kind of a doppelganger of consciousness.

Modern consciousness is represented by the perspective of an observer who detaches himself from the world to observe it objectively. While making observations, the consciousness of the observer is acknowledged as being distant from the world, as if he was seeing the world from its outside. In other words, consciousness seems detached from the body and the world. This is the true identity of ghosts. That is to say, one’s own consciousness is the very ghost that haunts a person. Consciousness keeps haunting a person even when one moves from one place to another, just like Yurei =Ghosts.

What is interesting is that Yanagida’s primary focus was not in ghosts but in Yokai’s. He said that Yokai’s haunt places. This means that the individual characteristics of each place inevitably influences life and thought. This function is more apparent in places that have negative character, lacking in any positive value—for instance humid swamps. Yokai’s appear when these negative qualities are given positive shape.

Yokai’s show up in many folk tales, but no matter how ridiculous the story, the Yokai’s retain a sense of reality that cannot be dismissed. This reality stems from the physical properties of a specific place, especially the negative properties that humans often struggle to incorporate. Although we cannot explain rationally using words, it is evident that our bodies and minds are influenced by such properties. What we see is another circuitry embedded in our bodies and minds. Our consciousness inevitably gets caught up in a reality that we wish to ignore, but is hard to deny. This reality is based on the physicality of the body—which is to say, mind as matter.

Ghosts a based on individual consciousness. Yokai’s, however, are attached to places and processes where the essence of an object’s behavior and the body correspond in an immediate manner. This differentiation seems to resemble the distinction Steiner made between the soul and the spirit.

A Ghost who is involved in an individual corresponds to soul, and Yokai can even be thought as the Japanese translation of the word spirit. It is not that humans make vessels. The human body and mind are themselves vessels.

In Japan, the dusk or twilight is called Taso gare. (誰そ彼) The literal translation of this word, Taso Gare, would be“ Who is He? ” “Who might this be?” In the faint darkness of the dusk times where day transforms itself into night, the identity of everything becomes, momentarily, ambiguous. “Who might this be?” When seen from the other side, it is not even clear whether I am myself. It is at times like these that Yokai’s appear. Or, more accurately, the mind of a Yokai which had been restrained until then makes an entry. Just like we briefly experience the origin of art while wandering inside Fujiko Nakaya’s fog. Yanagida aimed to place the basis of literature in this Taso gare where all identities merge as one.

The literal translation of this word, Taso Gare, would be“ Who is He? ” “Who might this be?” In the faint darkness of the dusk times where day transforms itself into night, the identity of everything becomes, momentarily, ambiguous. “Who might this be?” When seen from the other side, it is not even clear whether I am myself. It is at times like these that Yokai’s appear. Or, more accurately, the mind of a Yokai which had been restrained until then makes an entry. Just like we briefly experience the origin of art while wandering inside Fujiko Nakaya’s fog. Yanagida aimed to place the basis of literature in this Taso gare where all identities merge as one.

Kunio Yanagida’s work exerted a big influence that extended beyond the research of culture, reaching novelists and artists. The figure of something familiar suddenly turns into something uncanny. The given contours of things disintegrate, and a variety of Yokai’s make their appearance, igniting exchange with other unknown forms of thought.

When placed in a global context, Yanagida’s work corresponds to that of the Brothers Grimm or Herder. From his contemporaries, Yanagida’s work also connects to the literature of Franz Kafka. A literary work is never written by “me.” Whenever one tries to narrate something using words, a variety of small narrative forms inevitably flows into the writing through the medium of language. Literature is therefore written by these innumerable Yokai’s.Sprits, The act of writing, or narrating, transforms the writer. Language serves as a medium.

What is interesting is that in art, it was modernity that re-discovered the pluralistic sensation that the human body and mind already received, which the seemingly indigenous and primitive culture encompassed. This was in parallel to the discoveries of Natural Sciences.

The literature of Taso Gare—of “who might this be?” The reality which is hard to resist despite being ambiguous was the exposure of potentiality that governed our mind—an exposure of an unacknowledged, open network.

I have deviated greatly from the topic of abstract art and the question of whether something can be seen or not.

But when one considers the basis of abstraction, it become clear that what was questioned in the act of “seeing something,” was the fixity of status concerning the subject and the object, or the spirit and the material word. Even before observation from afar took place, the mind and the world were already mutually immersed in, and influencing, one another through multiple circuitry. What Yanagida, Natsume, and Yanagi shared was the awareness that the acts of expressing something, of making and narrating something, were not conducted by oneself alone, but emerged as an output of such network. Instead of me talking about the environment, the environment narrates itself, and appears as such using “me” as a medium. My mind (as well as my body) is itself a medium for the interaction of various circuits.

By the way, what I always wonder about Hilma Af Klint’s works is that her abstract art reaches its full bloom, both in terms of quantity and quality, around 1908, right before she first met Steiner. After meeting Steiner, human figures reappear in her paintings. When Klint formed a group with four other women, and experimented exchanging each other’s consciousness and the consciousness outside, her paintings seem to indicate the environment itself. Why did human figures reappear after her meeting with Steiner? Even if that human figure symbolized the correspondence between humans and their environment, or between the micro and macrocosm, she no longer made abstract works that seemed to embody the will of environment itself.

In art, anonymity or autonomy of the work (detached from its creator) was an ideal that many modern artists acknowledged and pursued. Abstract art realized this ideal. However, if humans are to desperately cling on to being humans, the only way to deal with such autonomous artworks would be to once again reduce them to humanistic description, to situate them within the order of language and explain them accordingly. But it seems certain that the understanding of knowledge as environment, or as network can never be attained if humans are not freed from being humans.

I first mentioned that abstract art began with ”the doubt towards the visible.” Vision or audition are mere secondary qualities, to use the terminology of philosopher John Locke. However, the core idea which gave birth to abstract art consisted in grasping the concrete character of objects, which are of course pluralistic, that such secondary qualities fail to grasp.

The nature of abstract art does not solely consist in being seen or heard by humans. A painting that does not depend on vision, music that cannot be heard. Abstract art taught us to admit such beings that transcended secondary qualities. Like a fog or a forest, or like the existence of our own bodies, such supersensible beings can be more directly and concretely sensed, even when they cannot be seen or heard in their entirety.