first appearance: Letters Sent from Heaven Ultima Academy Seminar at Mellomstasjonen, the new National Museum (Oslo), 9.Sep.2017

Dr. Ukichiro Nakaya, known for his research on snow, also had a broad interest in art. For instance, besides his accomplishments as the scientist, he is known to have founded the genre of “science films,” as well as established the Iwanami Film Productions, which became an important catalyst for the new Japanese post-war films. Like the Italian Neo-Realism, the method of documentary films developed at Iwanami Films became one significant source for the creation of new films in post-war Japan.

For Ukichiro, experiments in film and experiments in science were deeply connected. I would like to call their common ground: “the securing of indeterminacy.”

The reason why documentary films are more thrilling than fictional ones, is because what happens and what gets revealed in the film, as well as how it ends, is indeterminate even to the maker of the film. The act of watching the film ,therefore overlaps directly with the process of exploring an indeterminate reality. This indeterminate process is what makes the film real, thrilling and full of information.

Ukichiro who had created the science film“Snow Crystal” in 1939, established the Nakaya Laboratory Productions in 1949, which would later develop into the Iwanami Film Productions.

It is interesting to note that the music for Ukichiro’s first film “Snow Crystal” was composed by Akira Ifukube, who was famous for composing the music for the post-war Japanese film “Godzilla.”

“Snow Crystal” ends on a mysterious tone, admitting, “No definite conclusions can be reached.”

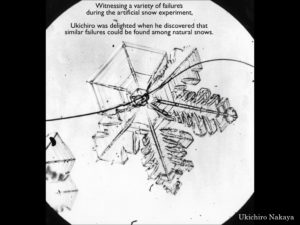

Indeed, by being open to indeterminate endings, science can be the ultimate mystery. The uniqueness of Ukichiro’s research consisted in his discovery of the fact that there are only few snow crystals with a perfect geometrical shape; that most of them are deformed through particular processes of mutation. In a sense, a drop of snow resembles Godzilla, an unpredictable creature born out of mutation.

Ukichiro’s well-known research on snow was inspired by the photographs of “Snow Crystals” which Wilson Bentley published in 1931. But from his own experience of photographing electrostatic discharges, he also had serious reservations about Bentley’s work.

Bentley had selected only the beautiful crystals out of all the variety of snows that exist. In other words, he had made choices based on human aesthetics. Ukichiro also noticed that Bentley had cut off the surroundings of snow crystals.

In this way, Ukichiro perceived a certain threat, or danger, in the works of Bentley. For, as he writes, the idea that snow can only be an aesthetically complete object, would delay the scientific study of snow considerably. Through , Ukichiro became aware of the distinct character of his ideas and understandings about the possibilities of the photographic device, developed through the methods he acquired through his electromagnetic discharge research.

“What a brilliant failure!” Ukichiro would scream every time he encountered one of these incomplete snow crystals.It was this

kind of snow which failed to be symmetrical, this incomplete and asymmetrical snow,

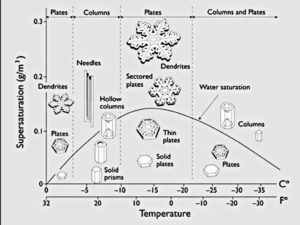

that Ukichiro focused on. Immediately after he started exploring the nature of snow, Ukichiro realized that there are much more kinds of snowflakes than Bentley’s photographs suggested and that they could be organized systematically.

When he succeeded in building the apparatus to make artificial snow, the parameters at work during the process of making snow started to become apparent: water temperature, room temperature, and time. The famous Nakaya Diagram brings together the fruits of his research.

What kind of process is necessary in order for one snowflake to appear? This was the question

that interested Ukichiro. No matter how ill-shaped a snow was, there was a  necessary process that gave birth to its form—in the words that Paul Gallico used later on in his novel “Snowflake”(1952), this was the “Life of Snow.”

necessary process that gave birth to its form—in the words that Paul Gallico used later on in his novel “Snowflake”(1952), this was the “Life of Snow.”

On the other hand, the thought which places value only on singular, ideal crystal forms, leads to the thought which attempts to eliminate all things ill-shaped.

It is possible to understand from all this, the reason behind Ukichiro’s famous proposition that 「雪は天(Ten)からの手紙 ─ “a snow is a letter from heaven.”

Information lies within the uniqueness of each ill-shaped snow, each of which is different from one another. It informs us about the process the snow underwent to arrive to us—it reports to us the life of snow.

But what does this “heaven (‘Ten’ in Japanese)” mean? The letter is written by heaven, which thereby endows it its meaning. The Chinese term “Ten” which Ukichiro used originally meant “nature” itself, as well as the laws pertaining to nature. By extension, it also became used as a word to address the sky.

The broadness of Ukichiro’s work was exceptional, but his wide interest towards culture in general was something he inherited from the intellectual community of the late Meiji period which included scientists, philosophers, novelists, and artists. At the core of this community was the notion of “indeterminacy.”

The person on the left is Ukichiro Nakaya, and to his right is his teacher, the physicist Torahiko Terada.

Terada was a scientist of statistical mechanics, who worked on various researches like the study of cracks in things. He was also known as a great writer who could expand scientific insights to the broader criticism of civilization. Torada was thus an intellectual who represented the open culture of the early Taisho period(1912-1926). Like Ukichiro, Torada also made paintings, wrote poetry, and played music.

Ukichiro started off his career by following the research of Terada, and delved into the study of electrostatic discharge (fire spark discharge).

The photographs on display for the current exhibition in Oslo were made during the process of this research. The experiments of discharge using the Wilson cloud chamber, and the photographic documentation of these experiments constituted the beginnings of both his scientific research as well as his unique approach to visual imagery.

Going further back, Terada’s teacher of literature was Souseki Natsume, the leading novelist of modern Japan. Souseki Natsume considered literature as portraying the process through which a variety of deviances or distractions of the senses, or fissures of emotion, are aligned to flow in one direction, until they form a fairly coherent consciousness.

Soseki analyzed literature using a scientific, philosophical method. His formula of F+f is well known.

The lower case f stands for the innumerable feelings that one perceives, whereas the upper case F stands for the particular focus imposed upon the multitude of such sensory impressions. The multiple feelings perceived are unified through particular focus 27—Soseki’s problematic may be seen as being influenced by the empiricism in Britain, where he studied.

But for Soseki it was literature that took on the form of F+f. Since it uses pre-established language, Soseki thought literature is given focus through notions indicated by words.

Therefore, the task in literature becomes how to add particular sensory content to the notion that is already shared as language. That was the meaning of the formula F+f.

Given this train of thought, the problem for Soseki was whether the focal point of consciousness which unifies multiple senses is brought from outside, or generated from within. What is certain is that self-consciousness was not something obvious for Soseki. My will always arises as a sudden whim. Whether Focus is derived from feeling or feeling becomes attached to Focus, remained indeterminate. According to Soseki, literature expressed this wavering process.

Soseki was active as a novelist for about 10 years, at the very end of which he presented an outline for new literature. This was a kind of a probability theory. It appeared in Soseki’s last, unfinished novel “Mei-an (Light and Darkness).”

From the start of the novel, the protagonist, who suffers from a chronic disease, wonders how nothing about his own actions or mode of thought is predictable. For instance, he feels that his current status of being married is only derived by chance through many causes that he is unaware of. He thinks it is quite like the theory of indeterminacy or the three-body problem by the mathematician Henri Poincare that a physicist friend—believed to be modeled on Torahiko Terada—told him about. Just like the difficulty of calculating the orbit of planets in a solar system with multiple stars, the determination becomes impossible when the causal parameters increase.

The choices that seem to stem from free will, or even free will itself, may be generated in such an indeterminate and contingent manner.

Like the three-body problem or the orbit of planets described by Poincare, the novel “Mei-an” depicts the situation where multiple individuals examine one another’s minds, thereby exposing everyone to mutual influences—what appears to be individual determination is actually derived from the complex dynamics of interference between multiple people, and the original cause of determination remains unknown.

The novel “Mei-an” remained unfinished by Soseki’s own death after much struggle with a serious stomach disorder. But as already mentioned, it was meant to embody the new literary form Soseki had envisioned. Soseki described this new ground using the neologism “Soku Ten Kyo Shi.”

The literal meaning of this term would be, to abandon the self (Shi), and follow the heavens (Ten). But does this imply, in tune with the banal imagery of Eastern philosophy, the demand to abandon the individual and return to nature? There are people who think that was what Soseki had in mind in his late years.

However, Soseki had previously discussed “individualism,” and claimed “self-centeredness”based on the fact that it is impossible for a person to think about the nation all the time. His interest was rather in where an individual’s free will stemmed from. When one takes into consideration the structure of “Mei-an,” in addition to Poincare’s theory of indeterminacy referred to in the novel, it is clear that the Eastern philosophy which corresponds to them is that of the I-Ching or the Book of Changes. The title Mei-an, refers to light and darkness—precisely the ying-yang

that was placed at the core principle of the I-Ching.

As I already explained, the word ‘Ten’ generally indicates nature, but when the definition of nature is not clear, it becomes thought as a generative process that follows materialistic necessity, in contrast to the willful mind. Then the command “return to nature” would mean to abandon conscious decision and return to the automatism of material necessity.

However, in the Book of Changes, ‘Ten” is understood as a more complex structure. Ten is a network generated by corresponding multiple structures. The contingency in nature may appear to be derived from a singular structure, but is actually a necessary result of the networking of one structure with many others. It is not determined within a singular structure. What appears contingent from one perspective, appears as a necessary choice from another. Free will is located where these two perspectives intersect. Free will is an effect created by the mutual correspondence and nested influence of these multiple perspectives.

The insight found in the Book of Changes goes beyond the dichotomy of spirit and nature. There is will inside nature as there is exterior environment inside the spirit.

What Soseki discovered through introspection was the existence of innumerable systems inside his own body and mind that each received, was influenced, and responded to, various information from outside without himself being aware of the process. In other words, the environment resides within oneself, and responds to various demands and intentions created from the structure of nature. “Ten,” for Soseki, was such a network described in the Book of Changes.

Baien Miura, an exceptional scientist/philosopher from the Edo period, visualized the nested network of heaven and earth, ying and yang in the most refined manner.

Where does free-will come from? Where does self-consciousness arise from? If one adhered to the dichotomy of “spirit = freedom” and “matter = determinism,” seeing the basis of free-will in the material world may seem to be a contradiction. But by thoroughly dismantling the spirit through introspection, Soseki arrived at the conclusion that free-will is based on materialistic indeterminacy.

Ukichiro’s description of snow as letters sent from heaven, meant that the contingent generation of deformed snows are all based on necessity, and one could read therein the mutual interference and correspondence of multiple structures. That was what he called “Ten.”

✴

What I think in regards to recent abnormal weather.The greater human being’s involvement in nature becomes, the more nature (phenomena) becomes unpredictable for us.Through the influence of such natural environment, and weather conditions, one’s own health becomes unpredictable and impossible to manage. Allergy (I am talking about myself).The paradoxical outcome of increase in human’s control of nature is the foregrounding of how humans are controlled by nature, and how this control is itself unpredictable. The fact that nature makes humans think rather than humans thinking by themselves has become more prevalent now.