On December 31, 2018, I flew from Tokyo to New Delhi. I had just finished the manuscript of my book on the American multi-instrumentalist and composer David Tudor which had kept me occupied for most of that year, and my son Aevi, who usually keeps me occupied when my work does not, was away in San Diego spending winter break with his mother and brothers. Having thus secured time for myself, I decided to travel in India for three weeks. Since I was immersed in writing until the very last minute, I had made almost no plans for the trip. The only thing I had decided in advance was to visit at some point the holy city of Varanasi, a place several different people on several different occasions and for several different reasons had strongly recommended me to go. Or at least that was what I thought. But actually there was one more thing that had been decided beforehand: I was scheduled to give a presentation at the gathering of Kagakūkan the day after my return to Tokyo. Because of this prearrangement, coming up with something clever to say on that occasion was on the back of my mind as I traveled. On January 24, 2019, I had safely returned to Japan and kept my promise by reporting on some of the observations I had made over the course of my travel. The following is a written version of that report, slightly extended and rendered into English (for performativity’s sake).

It was only after I arrived in New Delhi on New Year’s Eve that I checked the train schedule and found out that all the tickets to Varanasi for the next five days or so were sold out. Not wanting to spend so much time in the busy and contaminated nation capital (I have asthma), I decided to get on the first available bus going out of town. It happened to be a southbound bus heading to a place called Jaipur.

During the six hours of bumpy bus ride there, I educated myself about my destination. The city of Jaipur was named after Jai Singh II, the Maharaja who founded it in 1727. This respected ruler had a strong penchant for the sciences, and was in particular well-versed in mathematics, architecture, and astronomy. Soon after constructing extravagant palaces in the heart of his new capital, he proceeded to design and build a series of giant astronomical instruments nearby. Nineteen in total, they are collectively titled “Jantar Mantar”— which translates rather dryly in English to “measuring instruments.” It was the first thing I went to see when I got to Jaipur. [Fig. 1-3]

Their prosaic name was befitting, for precise measurement of where the stars were and how they moved was absolutely necessary back in Jai Singh II’s time in order to make important decisions such as when exactly the Mughal emperor (i.e. the ruler’s ruler) should start his trip—similar to how the whereabout of my son determines when I can start mine, except that the faraway stars could never be physically reached to begin with. In order to obtain knowledge of the world he had no access to, Jai Singh II gathered as much knowledge as he could from the world he did have access to. He set out to learn various forms of astrology old and new, from the ancient Greeks to the later Muslims, examined the magnificent Ulugh Beg Observatory in Samarkand, and perused the more recent European texts of Galileo Galilei and Johannes Kepler. As a result of all this, the instruments he built (or more precisely, had people built for him) attained a remarkable degree of precision for its time: the 27-meter giant sundial Samrat Yantra, aka the Supreme Instrument, for example, casts a shadow onto its arcs labeled with tiny markers allowing the measurement of time every two seconds. [Fig. 4]

In spite of the marvelous individual differences between them, I realized that all the instruments of Jantar Mantar shared two commonalities. First of all, they were all giant. It was Jai Singh II’s belief that the larger the instrument the more precise. Aside from being larger than humans, many of them were designed to have the user/observer inside them, serving as vehicles that one could ride on. Hence, a warning sign is now placed for later-day tourists: “Do not climb on the Instruments.” [Fig. 5]

At the same time, these giant instruments were also coordinated to something still more giant. For instance, the gnomon of Samrat Yantra, (a) points to the pole star which is aligned with the northern axis of the planet, (b) is angled precisely at 27 degrees to align with the latitude of the city of Jaipur, and (c) traces with its arcs the celestial equator which is a projection of the Earth’s equator onto the heavens. In other words, to access the otherwise inaccessible stars from afar, the measuring instruments which carried human observers as passengers used another instrument which carried them as passengers—the Spaceship Earth, so to speak. [Fig. 6]

The audio guide I listened to informed me that Jantar Mantar had met a quick decline after Jai Singh II passed away in 1743, as more inexpensive and portable telescopes became available. The vehicle-like instruments which took recourse to our vehicle-like planet were outran by instruments which could be more easily transported from one place to another on actual vehicles. It turns out precision could be sacrificed for the sake of efficiency. But my guidebook informed me something else: that Jai Singh II’s measuring instruments are still being used today by the local society of astrology—whose office, I discovered later, is located just around the corner from Jantar Mantar. [Fig. 7]

After spending two days in Jaipur, I headed to a city called Ahmedabad where I engaged in some extra research following the footsteps of David Tudor who had spent some time there on several occasions, even building the first electronic music studio in India during one of his stays in late 1969. After finishing a series of scholarly detective works, I decided to travel eastbound to go see the ancient ruins of Ajanta and Ellora, world-famous Buddhist cave temples carved into two rock-face mountains near another city called Aurangabad. [Fig. 8]

The 30 or so temples at Ajanta are older, built between the 2nd century BCE and 6th century CE, while the 34 or so temples at Ellora date from the 6th to 11th century, conveniently taking on where the former leaves off. So together, these two sites offer a rare opportunity to observe the stylistic progression of Buddhist art over the course of 1000 years in quick succession. Luckily, I had decided to go to Ajanta on the first day and Ellora on the next, without realizing that I was following their chronology. But since I understood that was what I was doing once I got to Ajanta, I decided to ignore the local taxi driver’s friendly advice to see the most famous temples first and leave the rest for later, “because they are just more of the same thing, and [I] might get tired.” Instead, I rigidly followed the chronological order of the caves in each site, moving from the older to the newer and retracing the history of Buddhist art in this manner.

At one point, I began to conceptualize this experience in relation to Jantar Mantar. For if Jai Singh II had created astronomical instruments that enabled the observation of what is spatially on a scale much larger than most things in human life, Ajanta/Ellora were archaeological sites which allowed the observation of what is temporally on a scale much larger than most things in human life. The giant instruments and the Buddhist caves each condensed vast time and space to align with experience on an average human scale. But as far as time was concerned, the perception each allowed appeared to be diametrically opposite. Instead of the second to second passing of time on a giant sundial, what I saw in Ajanta and Ellora was transformation across a millennium in fast-forwarded mode, as if I was flipping through a flip book.

But in order to explain the details of what I read, I must take you through another flip book first. For some time, I had been interested in the life and teachings of the Buddha, né Siddhārtha Gautama. The basic facts are well-known (to the extent that Masaki Fujihata sitting next to me loudly commented, “everybody knows that” when I got to this part in my presentation. But my concern is just who this “everybody” that the relatively well-known media artist appears to think he is entitled to mediate is, as I will get to later) and can be fast-forwarded: Gautama was born in the 5th century BCE as a prince. After spending his childhood and early adult life inside a palace filled with luxury and pleasure, he felt the emptiness of it all and decided to leave his family and wealth. What he sought to find was a way to overcome the seemingly eternal cycle of suffering and karma taught in Brahmanism, the prominent religion of the time (which later became Hinduism). After six years of intense ascetic training during which he deliberately committed both his body and mind to all kinds of extreme suffering, Gautama saw that he was not getting anywhere and quit. It was soon afterwards that he finally attained enlightenment. Having experienced both extremities of pleasure and pain, he concluded that neither served his purpose well. The answer lay in the “middle way”—neither pleasure nor pain, but a refusal to participate in the process of reproduction, whether this be social and corporeal.

What interested me about Gautama’s life story is how everything he taught was based on his strictly empirical observations. He preached not because he was God’s son or a prophet who had been given God’s words, but because he had experienced a radical shift of perspective, and was willing—although reluctantly at first—to let others experience the same if they wished. So the value of what he preached lay not in its connection to a divine other world but in the fact that it was tested and proven to work inside this one. His solution for suffering did not rely on the power of transcendence. His words functioned more like performance instructions which, when followed, led the performer into enlightenment. As far as I could see, what the Buddha preached was a path to salvation that did not take recourse to religion.

Back at Ajanta and Ellora, however, what was unfolding before my eyes was what had happened after Gautama passed away: the gradual process of his anti-religious teachings turning into a religion of its own. And this was most evident in the sculptures. Although the Buddha had strictly prohibited his disciples to make any representation of himself to prevent his teachings from becoming a transcendent object of worship, dome-shaped monuments storing his bones called Stupas began appearing almost immediately after his death. [Fig. 9]

As I moved from one cave to another following their timeline, sculptures of the Buddha himself began to appear in temples built around the 1st century CE, reviving the figure of Gautama almost 500 years after his death. So much for his absolute conviction that he had discovered a way to end the doomed cycle of rebirth once and for all. [Fig. 10]

Over the course of the next couple of centuries there was a gradual proliferation of deities. Especially notable was the growing presence of the female Buddha, Tara, who first accompanies the male, but later acquires her own centrality. [Fig. 11-12]

In more later temples, even the hierarchy between the male and female Buddha was often reversed, or the two were paired as an amorous couple. [Fig. 13-14] At the same time, sculptures which were until then predominantly in static position, either sitting cross-legged or standing straight up (as one surely cannot attain enlightenment while moving around) began to take on more dynamic postures. 1000 years after Gautama’s death, Buddhism appeared to have come a long way from its initial disapproval of reproduction and disgust towards all things carnal.

As I watched, I began to wonder if there was any connection between the emergence of Buddha as a figure and the fundamental transformation of Buddhism that also occurred circa 1st century CE. Around that time, a new sect had emerged criticizing the egoism of previous monks who focused only on the pursuit of individual enlightenment. They instead proposed the salvation of all sentient beings. This new branch called themselves the Mahāyāna, which translates to “Great Vehicle,” and ridiculed the earlier school by calling them Hīnayāna, or “Small Vehicle,” in comparison as it could only deliver one passenger at a time to salvation. Like Jai Singh II, they reasoned that the bigger the vehicle the better.

What the Great Vehicle had successfully accomplished was to convert the Buddha’s teachings into a systematic ideology with all the stereotypical traits of religion. On one side were deities who are (usually) inaccessible to humans; on the other, there were humans who longed for salvation through the graceful intervention of such divine powers. As a religion open to all people, there was a need for the Great Vehicle to attract, allure, and entertain its passengers, as if they were a tourist agency, which seemed to explain the emergence of the sculptural representation of the Buddha as an object of faith, followed by the gradual incorporation and emphasis of carnal elements against initial prohibitions.

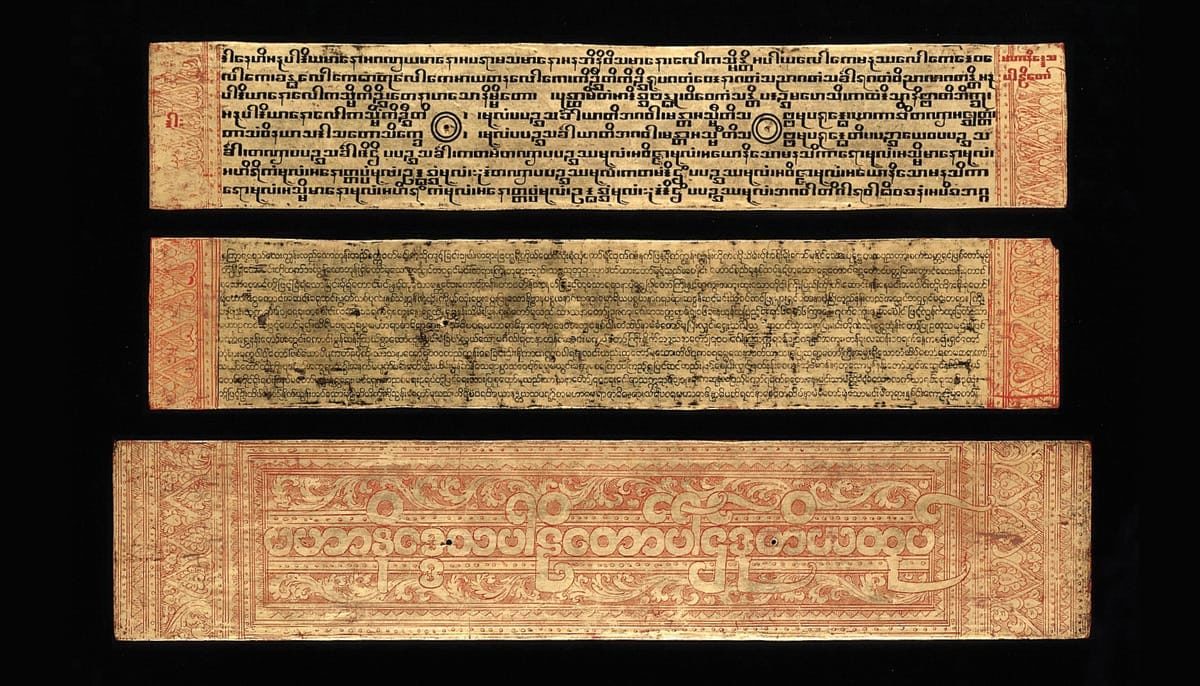

Understandably, this reformation was met with huge resistance from within Buddhism. Not only were sculptures destroyed, but the texts that have been passed down to us as preserving the words of the Buddha himself in relatively pristine form—the so-called Pali Canon—were actually first written down around the same time as the development of the Giant Vehicle. The aforementioned performance instructions were thus part of an effort to bring Buddhism back to its origins, even if that meant fabricating them anew. They were linguistic vehicles of counter-reformation that promised to take the reader far, not so much in time and space like Jantar Mantar or Ajanta/Ellora, but in the very conceptualization of time and space. For once enlightenment is achieved, as far as I could understand from my own reading of the Pali Canon, one is fully present but no longer there. Past and future cease to matter outside the cycle of reproduction. [Fig. 15]