first appearance: “Anarchive n°5 – FUJIKO NAKAYA FOG 霧 BROUILLARD”, 2012

In common speech, the first person to draw the fogs of London is held to be the British painter Turner. This saying requires a footnote of correction, however, for Turner did not paint fog as a natural phenomenon, but instead chose as his subject the way in which fogs indiscriminately mingled with the artificially created steams of the newly invented steam engine. Indeed, a careful inspection of Turner’s paintings such as “Rain, Steam and Speed” (1844) will reveal that these two, initially indistinguishable types of vapor are brilliantly differentiated by his brush.

Meteorological variations like fog or clouds had until then never become the subject of paintings. Their amorphousity makes them difficult objects to draw. Ever since the Renaissance, clouds never exceeded being mere substitutes to fill in the blanks of the canvas. If paintings after the Renaissance (through the introduction of perspective) succeeded in mapping three-dimensional spaces onto the entirety of the canvas, it follows inevitably that even the blank spaces have to be a depiction of something. In other words, the seemingly void blanks are nonetheless filled with invisible air, depth and thickness. From then on, water vapors such as fogs or clouds were diminished into expedient fillers (injected onto the blanks of the canvas) to tentatively infill in this invisible depth of air/space. Because clouds (vapor) cannot be determined as form, they could become convenient quid pro quo for the similarly indeterminate space and the depth it was thought to contain. Without any vigorous efforts to paint, the uneven tone created by ambiguous and capricious coloring is considered to represent the hovering clouds in that space and effectuate depth — clouds and water vapor constituted such a handy representation.

In order for clouds and fog to ascend from their status of mere supplements of canvas margins into true subjects of paintings, it was necessary that they become namable and measurable. In the eighteenth century, the British meteorologist Luke Howard proposed the first systematic classification and nomenclature of clouds, making it possible to structurally read their altered formation.

Following Howard’s path, the painter John Constable brought home the fact that the forms of objects are dependent upon the method of cognition, and set on an endeavor to reposition pictorial depiction as scientific observational methodology, even if this forced him to deviate from the traditional form of paintings. If conventional pictorial forms distort scientific observation in favor of its own coherency, paintings should rather dismantle themselves into thousands of sketches which are effective scientific data (as is well known, the qualitative difference between Constable’s tableaus and sketches derived from this issue).

Needless to say, however, Luke Howard’s theory of clouds is not reduced to the mere issue of “how to draw clouds in paintings” (nor its application limited to answering the question of “how to organize the blank spaces of paintings as representation”). By grasping them as structures which respond to climate conditions, he instead created a morphology which enabled the understanding of the altered formations of water vapor despite its constant flux and lack of fixed and rigid contours. The initial subjective impression that molds a shape out of an ever-changing phenomenon must be recomposed into a structure corresponding to that of the weather. Specifically, Howard conceived of a descriptive system which renders the kaleidoscopic modality of clouds into a combination of four basic patterns that correspond to differences of climatic structure. And he gave each of these four basic forms of clouds a name. It was through this act of nomenclature that clouds which hitherto seemed to change by chance, started to appear with a precise form and its vicissitude was grasped as structures. Howard thus succeeded in creating a correspondence between the cognitive structure upon which subjective senses are built, and the structure of natural phenomenon. Form is assigned a stable position for the first time by this structural correspondence.

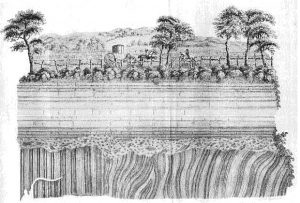

Howard’s proposition claimed a temporal (rather than spatial) structure which could localize clouds’ endless change as form.Therefore it was the founder of morphology, Goethe, who attained an accurate grasp of the possibilities inherent in Howard’s theory of clouds, in parallel to the geology of Abraham Gottlob Werner and James Hutton (transformations that occur over vast temporal scales in geology appear condensed as instant changes in climate).

With Goethe, a form was conceived as segments or crystals discovered as stratification, interference or fault throw of formational processes occurring in countless different temporal cycles (ranging from vastly long to extremely instantaneous scales) contained in nature. Form never stops its change or growth. Its secret lies within the structure of altered formation that the various temporal cycles create, and not on the side of cognition which terminates this process. One should rather read structure out of altered formation and render instead his own static cognition into the same transformational process (by incorporating temporality therein).

The mechanism of clouds as morphology — this was the formational principle not of pictorial representation, but rather of sculpture. Goethe’s morphology presses change upon none other than the classical, static form of sculpture theorized by Johann Joachim Winckelmann and others. Despite the precedence of sculpture over paintings in his theory, Winckelmann deals only with forms of representation. The demand for static form arises out of mere convenience (deficiency) of human cognition. Morphology, on the other hand, is an attempt to approach the structure of ever changing phenomena (which includes human cognition). Morphology as the (formational) principle of sculpture. In other words, geology and meteorology as principles of sculpture. The form of sculpture is thus reconceptualized as temporal form. Against the claims of Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, a sculpture is none other than a temporal art. More accurately, it is the form of sculpture, its principle of formation that creates temporality (which is merely a subjective form).

To treat them as form or object, the distribution and density deviations of small water particles such as clouds or fog necessarily change the sensibility towards objects per se. Objects are no longer solids, but merely contingent beings which are phenomenalized stochastically by deviations in between overlaps of various parameters. Deviation known as density (potency) is energy and creates movement. The cognition of forms is based solely on this movement process. In other words, the cognition of “seeing something” is also a movement and a part of the process. Form, therefore, belongs rather to subjectivity than objectivity. Nay, subjectivity is in itself nothing but a stochastic being composed by this (statistical) mechanical procedure. Subjectivity, in a manner of speaking, is the focal point or center of gravity which draws the contours of form together.

For instance, “impressionism” which was initially used as a mocking moniker turns out to be a precise appellation. For “impressionists” expressed ever-changing events as differences in the density of various elements including deviations of light and color. The form which appears there relies on the efficiency (convenience or choice) of the viewer’s retina.

The development of set theory, which aimed to encompass the association and transition of various concepts via limited elements and their distribution and density (potency), proceeded in parallel with nineteenth-century industrial revolution. Heterogeneous distribution tends to (and should) move towards a homogenous state. Heterogeneous deviations phenomenalize as difference, collision or conflict between disparate concepts (or characters of actual things). Therein exists the source of power and potency. It goes without saying that such (statistical) mechanics rose to dominate technology and politics since the nineteenth century. Morphology thus becomes connected and develops into political mechanics. It could even be said that “impressionism” and “cubism” (which should be understood as morphology to begin with, and not a form of representation) both conformed to this trend (Felix Feneon, for instance, was one of the rare critics who were aware of this).

At the outset of twentieth century, Soseki Natsume (1867-1916) who was to determine the shape of Japanese modern literature and culture to come conceived a literary morphology in his “theory of literature” (1907). Soseki theorizes literature as an art which provides a focal point F ( the concept as objectivity) to a cluster of dispersed scatterings of sensibility, interest and emotion — which he terms as f — creating density deviation and organizing the movement. The difference between literary forms can accordingly be described as a mechanical function of f and F.

Literature, in other words, is a technique for developing “subjectivity f” into “objectivity F” and controlling it. Written in a Japan that was amidst its way to becoming a modern state, Soseki’s literary theory obviously overlapped with his speculations on the formational process of the nation-state. For Soseki, the problematic of a nation-state in the process of formation at the time appeared to be a distinctively artificial endeavor, consisting in giving a focal point to the scattered cluster of each individual’s disparate spirits and dispersed sensibilities, or interests, in order to organize them all into a singular collective subjectivity (i.e. the “National Spirit”).

The distinction between objectivity and subjectivity does not exist a priori. It is only set by the function formulated stochastically. Soseki depicts the state of commingled subjectivity and objectivity as a constellation of modalities that water vapor demonstrates. In the novel “Kusamakura”(The Three–Cornered World ,1906), which seems to brim with art theory from cover to cover, a painter who dodged the draft has an epiphany on how to overcome the entire lineage of Western art theory (fixed dichotomy of objectivity and subjectivity) from Winckelmann to Lessing, amidst the steams of a hot bath in a provincial inn. It suddenly dawns on him that both subjectivity and objectivity are merely phenomenal modalities that appear from the stochastic distribution of various sensibilities, just like perception in the steams. It is political establishment and power (the most typical being the nation state) which fixes and controls this relationship (Soseki went on to explain the workings of state power using the analogy of the steam locomotive).

Twenty years later, the “national” sculptor Kotaro Takamura (1883-1956) who struggled at pains to radicate Western modern sculpture to Japan writes: “The sculptor wishes to grasp things. He wishes to see everything as if he were holding them in his own hands.” “The tactility of the sculptor tries to dispel the fog. And tries to palpate for sure the fact that a fog is a fog” (The World of the Tactile 1928). The fallacy is immediately clear. The sculptor (who self-appointed himself a national mission) is dedicated to the task of grasping and objectifying an object he has never yet directly held (and therefore is only imagined tentatively to exist). What in fact encloses his hands is fog, the ambiguous and elusive mist which he persuades himself (asserts) as being merely a fog, desiring instead to directly hold in his own hands the essential entity (i.e. the “National Spirit”?) which might just happen to be there once the fog is dispelled. Sculptor becomes here the giver of form to imaginary existences, the creator of empty monuments, and even a caricature of (the fascist) politician.

To maneuver the mass in the same way that the steam engine controls the movement of water vapor at will. It is this aggregate, this abstract entity called mass, deprived of specific characteristics and dismantled into homogenous particles (proletariat, consumer, citizen) that constitute the form of any (seemingly) substantive establishment. The variety of its expression has been found in elections, fascism and world wars (the all-out wars employing toxic gases, trenches, submarines, and entangling all citizens are no less than battles of “density”). If under the domination of such mechanics, Art were to sing it’s own praises for realizing a form which fixes and immobilizes all things (via the concept of harmony), this temptation will only approximate that of fascism.

Though Futurism may be too obvious a reference, the course from Cubism to Constructivism is directly linked, beyond mere analogy, to the trend of Social Constructivism much trumpeted today. It could also be said that over the time lapse of a hundred years, the assumption that the state and its citizens, or phenomenon such as the subject or human can be constructed as a mass, became established politically. Just as Luke Howard classified clouds, the orientations and trends of consumers are now classified into patterns (as can be seen on amazon.com’s attempt to sort out the interests of its customers). The category (concept) of sculpture or painting, in a similar fashion, is no more than a deviation or density of a set of particles (that is, the objectivity/concept F that Soseki talked about), following likewise the taxonomies that amazon.com, for instance, would employ. However, whether it is the state, currency or human beings (or art or literature), once a concept is identified and established, each (category, genre) would be convinced of its identity and thus desire for its sustainment. This indeed was the very power/potency that mechanics aim to use (and which creates profit).

Similar to the form of clouds, such distinction may not signify an inherent, qualitative difference; it may be a mere illusion phenomenalized stochastically as difference in density. But as all politicians know, the resistance, which may seem ethical, that such stochastic forms demonstrate to maintain their identity (in other words, dreams that phenomenalize into substance like the form of clouds), can inverse itself and turn into power, or the origin of violence, per se. It is none other than such deviations that create disparity, the difference of which then creates interest (i.e. profit) and potency.

An author who studied under Soseki Natsume, as well as being a famous physicist, Torahiko Terada (1878-1935) is known to have researched the physics of form based in statistical mechanics. Terada would, for instance, read the complexities of non-linear multi-dimensional temporal structures that constitute nature into cracks that ran on the surface of objects (in retrospect, cracks are what gave birth to Chinese characters). In one of his most well-known essays, “A Bowl of Hot Water” (1922), he depicted in a simple and refined style how the entire climatic phenomena (the whole universe) ranging from fogs, clouds, snow, hurricanes, airstreams, ocean flows, to monsoons, could be found along with its principles in the behavior of a small bowl of hot water (and steam).

First of all, there is a white steam coming out of the surface of hot water. This is obviously the hot water vapor that cooled down and turned into an enormous amount of small water drops which are huddled together, just like a cloud or a fog. If you take this bowl to the sunny part of the veranda, and lit the steam with sunlight placing a black cloth or something on the other side so that it is possible to see through it, you can see the larger drops of water flickering. (…) When a completely transparent gas vapor turns into a liquid drop, there is always something that becomes the core of that drop, around which vapor condenses and sticks, so scientists have found out that without such core, fog cannot be explained so easily. What becomes the core is usually something like a very tiny dust particle that cannot be seen even with microscopes. In nature, there are many of these floating in the air.

Terada, Torahiko, A Bowl of Hot Water, 1922[*1]

In 1934, when the entire nation was heading towards the preparation for war, and the whole public opinion was directed in its favor, Terada gently criticized the repeated notion of “national defense” from the standpoint of physics. What he wrote reads ostensively like a criticism on how drastic changes in nature or catastrophes (which often turn into disasters) occur from cognitive fallacies caused by men.

As civilization progressed humans gradually developed an ambition to conquer nature. Thus, they made various devices which fight against gravity and resist wind pressure or waterpower. But when Man is assured that he has contained the brutality of nature, just like a large herd of beasts who somehow breaks out of their cage, nature goes berserk, collapses the skyscrapers, bursts the levees, jeopardizes human lives and destroys their possessions. It is not inaccurate to say that the origin of this disaster stems from the cheap tricks of Men to rebel against nature. The one responsible for accumulating potential energy which converts into kinetic energy of the disasters, and thus has strived to worsen the damage is none other than civilized man himself.

Terada, Torahiko, Natural Disasters and National Defense, 1937

Needless to say, Terada regards changes in nature to be inevitable. Such changes are certain to occur, and could therefore never be unpredictable disasters. Disasters occur rather when human cognition and their establishments based upon it fail to respond correctly to these changes. In other words, disasters are tragedies caused by attempts to fix nature into forms and establishments that fit human cognition instead of accepting changes in nature. It is only a necessity that establishments and forms that are forcefully fixed should crumble.

The larger the terrain that the establishment aims to control and fix, the more grave the damage. This paradox inherent in the concept of disaster prevention is one that applies to the nation state which attempts to organize people with variously dispersed interests, sensibilities and origins into a singular (form of) citizen (as Terada’s teacher Soseki thought). Terada thus criticized “national defense,” the form of State control executed under the pretext of preventing war, by indicating the inherent paradox in disaster prevention. It is the very notion of “national defense” (and State control which accompanies it) that makes war necessary and becomes the cause of its outbreak.

There is one other drastic change in our relationship with nature that occurred due to progress of civilization. The organic conjugation of human associations, especially the one called State or Citizen, have very much evolved, and the differentiation of its internal structure notably developed, so that the possibility for damage in one part of such organism to create a seriously harmful effect to the entire system is more likely, and at times even the damage to a tiny part could become fatal to the whole.

Terada, ibid.[*2]

This logic of Terada became widely diffused in the dictum form, “natural disasters occur when you aren’t thinking about them” (because natural disasters are catastrophes created by the gap between the formation process or structure of nature and the cognitive structure of Men, they must always occur when they become forgotten). The details of which were revealed by one of the students of Torahiko Terada, the physicist, poet, and essayist Ukichiro Nakaya (1900-1962).

For Ukichiro Nakaya, who is known to have revealed the structure behind the formational process of snow crystals (Nakaya Diagram)formational process of snow crystals (Nakaya Diagram)

and to have created the first artificial snow in the world, form (being neither in the object per se nor the subjectivity of the observer) structured a once-in-a-lifetime encounter (fraught, between the observer and the object) within the variously changing weather conditions. And the one who sees a snow crystal (which never repeats the same form twice even if the formational principles stay the same) is no one else in any other time but the observer self of a specific moment (in other words, we humans fail to observe most of nature’s appearance, or fail to recognize even if we saw them).

For instance, ideally well-formed snow crystals that people call to mind (and photographers incline towards) almost never appear in reality. It is well known that W.A. Bentley’s photograph collection Snow Crystals played a decisive role in Nakaya’s choice to study snow. His interest, however, was directed rather towards the fact that seemingly perfect snow crystals like those Bentley photographed were actually rare to find. The process of nature rather abounds in crystals that have attained complicated metamorphosis and seem to have gone awry and irregular (and thus are ditched and forgotten by most people). What Nakaya Diagram revealed was the structure of the formational process of such mutant crystals. It was the failure or malformation of snow that contained more information for this physicist.[*3]

In the frozen laboratory, at fifty degrees below zero, holding one’s breath and witnessing the formational process of snow crystals — what becomes apparent in the uniqueness of each snow’s form (which, again, seem to be malformed at times) is the unrepeatable meteorological, temporal-spatial condition of that very place. The form of a snow is thus a fruit of the encounter (interference) between the various conditions and functions of uncountable parameters of nature. The entire once-in-forever setting of environment and modality is inscribed within the specificity of form (the world famous Nakaya Diagram reveals the structure through which snow crystals attain different forms according to specific climatic conditioning)

That is why Ukichiro wrote that snow crystals were “letters sent from heaven.” He discovered (just as the four eyed monster Cangjie who invented the mechanism of Chinese characters from the animal hoof-print) that snow crystals were equipped with a transformational structure, likewise to letters.

It was in the late 1960s that Fujiko Nakaya invented her fog sculpture. Once the formal principles of nature are known (namely, that form is not a fixed, but an unfixable structure created by the observer and object), it becomes difficult to be accustomed to Art as a form which immobilizes time. It must have been all the more so for Fujiko, who grew up close to her father Ukichiro devoted to understanding the extraordinary process of crystallization that nature engenders.

Just as Paul Klee thought, the process of overlaying colors and joining lines during the course of creating a painting indeed resembles the formational process of nature (To paint is an event in itself, and Klee therefore conceived the act of seeing a painting as thinking with eyes along the temporary formation process layered upon the canvas). But artworks ultimately betray this process and immobilize the time of nature.

The reason snow crystals appeared extremely alluring to the eyes of many, despite Ukichiro’s research, might have been because the transitory disappearing snow nevertheless attained at times an ideally complete form, a universal composition that seemed to transcend its status as natural form. If this appraisal was indeed so, then it must have been a mere aesthetic fallacy. For the lucidity and intensity of form found in snow crystals was merely a reflection of the ideal of humans who attempt to selectively find only what they wish to see. Ukichiro points out the following:

In this sense, it could be said that the development of microscope photographs momentarily held back the inquiry of snow crystals. The German meteorologist Alfred Lothar Wegener also referred to this interesting psychological phenomenon. To put it briefly, one refrains from taking what is not beautiful when he looks into the microscope. Because of this tendency to only photograph what is beautiful as pattern and planar, people were led to believe that snow crystals were all like that. Bentley is not the only person responsible about this.

Ukichiro Nakaya, ‘Snow Crystal’ conversations

The infinite formational process of nature wherein the crystal also in time melts and disappears, is completed the moment the snow crystal is photographed (the interminable process rendered into oblivion), and indeed reproduced to be used as the perfect ornamental pattern — just as “Kunstformen der Natur” of Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919) was applied, true to its name, to decorative art; or as the plant photographs of Karl Blossfeldt (1865-1932) who was heavily influenced by Haeckel were nature forms selected stylistically. The photographs of snow crystals that Bentley (who was the same age as Blossfeldt) took, likewise displayed forms that were carefully chosen and staged as an art style.

Snow crystals regarded as forms are no more than reflections of Men’s ideals and ideas: a mere objecthood (to employ the term that art critic Michael Fried used to criticize Minimal Art).

Fujiko Nakaya started her artistic career by engaging in exercises of color and composition based on Joseph Albers’, and then moved onto use structures of organisms such as protists, cell divisions, or plant roots as models for her works. It was only inevitable then, that in the late 1950s to 60s she started incorporating metabolism into her works (much earlier than artists like Robert Smithson who similarly focused on the irreversible temporal process in natural phenomena, and the interferences between various temporal cycles). Canvas that quickly start to decompose along time. Works that accept the process of material deterioration. She called them “decompositions,” instead of compositions. Involved in this unfinished project of Nakaya’s must have been her objection towards the concentration of people’s interests (the aesthetic reception) solely around the complete beauty of the ideal form of crystal while disregarding the process through which the phenomenon of snow is created, along with her protest against Minimal Art that had started to appear at the time.

Most natural processes are not definite as forms and cannot be grasped in a consistent manner. In comparison to ordinary aesthetics, they only seem brimming with confusion, they are chaotic and noisy. Forms remain incomplete and appear to constantly deviate from themselves and disintegrate. Put simply, most of nature does not appear beautiful in human eyes (as Torahiko Terada wrote, that is why humans aimed to control nature, by which they paradoxically destroyed it and induced natural disasters).

The confusion that only appears in human eyes, the deviation that the same eyes fail to grasp — these are sources of creativity and objects of intellectual research. Creation does not consist in arranging the form of nature to fit human cognition. It consists conversely in transforming the very cognition which confronts and observes nature.

For some time in the beginning of the 1960s, Fujiko Nakaya was invested in a project where she would overlay every kind of color onto a tableau, as if she were overlaying the interminable process of altered formation, only to cover it at last with burnt sienna (reducing the tableau to soil). This earth that appears in the end had in some parts been wiped its colors off with turpentine, implying the process of matter released from all forms dissolving into particles and flying into air. Also, vague mist or cloud was devised to show up in the blank spaces where color had been wiped off.

To accept (and deal with) the altered formation of things as they are (the snow crystal is only an instant event within the entire altered formation that water goes through), without aiming to fix them. It was also a necessity that Nakaya, after encountering E.A.T., a somewhat anarchic association of artists and scientists, became one of its core members, and conceived of constructing a machine to create fog as soon as she had the chance to collaborate with engineers.

A sculpture of fog — the essence of counter culture (who, today, might understand that?) is demonstrated in this work. It is a grave error to find mystifying and obscuring effect in the fogs that Nakaya creates. Many architects still conspire to use artificial fog (which Nakaya invented) to hide the figure of the unashamed objects they made and to cover the margins in the periphery of their buildings. For them, her fog sculpture is no more than a replacement for the smoke screen which conceals the arbitrariness of the object.

It is an even worse falsity to appraise the sole effect of fogs as “mystic,” etc. Such mystical effects are nothing more than iterations of Romantic illusion (escapism) conceived by painters like Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot (1796-1875), who saw in fogs the capacity to project the world beyond reality or subjective memory (as exemplified in works such as “Morning, Fog Effect”). In short, they are merely pictorial effects to fill in the blanks of the canvas (Chinese landscape painters -such as Guo Xi-who overlaid the altered formation of water to the formation principle of mountains and landform, and further generalized it as the principle of pictorial formation — which transforms ink with water —, criticized therefore the easiness of obfuscating forms via the effects of cloud and fog, and of staging mystical depth by heavy usage of water vapor. Fog according to them should instead be as firm as a rugged mountain).

It must be stressed that Fujiko Nakaya did not make an elusive sculpture/fog. What she made was “a device that generates fog as definite matter.” Her fogs are obtained by decomposing the continuous volume of fluid water into millions of mutually independent water particles with an extremely tight nozzle (water sprayed at 70 atm from a 16 micron diameter funnel crushes into the needle attached immediately above, shattering into 20-30 micron fog drops equivalent to that of nature). It is high-definition water. Because every water particle is independent from one another, they can each float and waft separately through the air. Their cluster is what people perceive as a phenomenon they call by the name “fog.”atm from a 16 micron diameter funnel crushes into the needle attached immediately above, shattering into 20-30 micron fog drops equivalent to that of nature). It is high-definition water. Because every water particle is independent from one another, they can each float and waft separately through the air. Their cluster is what people perceive as a phenomenon they call by the name “fog.”

Fujiko Nakaya took over and deconstructed the very power which creates the sculptural phenomenon (in comparison to Robert Smithson’s earthworks, for instance, which aimed to ground the same power onto the irreversible process of nature). It is neither the background nor the blank margins of form. It is rather the formation principle per se, or the structuralization of such process. Pointillism in sculpture? Nay, it can even be said to be the restoration of the lost philosophy of the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus.form. It is rather the formation principle per se, or the structuralization of such process. Pointillism in sculpture? Nay, it can even be said to be the restoration of the lost philosophy of the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus.form. It is rather the formation principle per se, or the structuralization of such process. Pointillism in sculpture? Nay, it can even be said to be the restoration of the lost philosophy of the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus.

And not only did Nakaya decompose water into fine particles, make them waft in the atmosphere, grovel over the earth, through the trees, and connect, obstruct or enfold people. The unpredictability of this moving form is just an illusion, a projection of the ambiguous cognition of the one who sees it (in fact, there is no ambiguity for Nakaya’s technology which calculates and maneuvers this movement of fog). The movement of fog is none other than the movement or fluctuation of the spirit. What actually exist there, are various movements of mutually independent, countless water particles (which respectively are each devoid of ambiguity, and are clear and swinging). Just like Epicurus thought, the true secret of human spirit’s freedom and intention lies in these unclouded (and uncountable) trajectories of diverse fine particles.

In retrospect, it seems that many artists in the 1960s, as if responding to the expansion of mass culture and the war in Vietnam which paralleled it, directly traced or drew figures that dissolved into the environment (of special preference was the blue sky) like heat hazes or shadows (its precursors were obviously Vietnam which paralleled it, directly traced or drew figures that dissolved into the environment (of special preference was the blue sky) like heat hazes or shadows (its precursors were obviously Rauschenberg’s blueprints, Yves Klein’s Anthropometries, and in Japan, the shadow series of Jiro Takamatsu (1936-1998)). If Pop Art was an ironic response to the era of late capitalism where individual personalities are decomposed and reduced to a mass of statistical myriad particles, the fact that objects melting into the blue sky as clouds became the most popular subject at the time might be interpreted as a critical claim that every real existence is as indeterminate as clouds in the sky, and that the distinction between illusion and reality is an arbitrary division based on the framework of the observer.[*4]

Fujiko Nakaya, however, never regarded “clouds” as a symbol of indeterminacy regarding undifferentiated reality and unreality (as has been mentioned repeatedly, it is such Romanticism or Mysticism that deprives humans of their creative and critical faculties). By decomposing water’s ambiguous continuous volume (i.e., mass) into clearly separated particles and then releasing each of those particulate movements, Nakaya organized an extremely lucid movement of the fog.

Without consigning mysteries or the transience of ever-changing world to fog, Nakaya created a device which dismantles such aesthetic desires/potency per se. What she grasped firmly was the structure that sustains the altered formation of objects, and what her device emancipated was the very potency or energy of free altered formation that the assembly of innumerable fine particles separated from one another create, which breaks through any rigidly fixed form. This endeavor obviously overlaps with the prospects of free activity which conditions the possibility of humans to be humans. Movement created by fog, or rather, by clusters of water particles — this is nothing other than firm free will.The cluster of myriad water particles that surrounds Pepsi Pavilion; that guides and dance along the dancers from Trisha Brown Dance Company; that follows and is followed, hiding beneath the pit in the ground and surprising the children at Showa Kinen Park — this is free spirit per se.

This also explains why Nakaya developed the activities of E.A.T. forming an organization to support the network of activities (precisely like the movement that water particles create) of various artists including herself, which she named Process Art. Such activities of Nakaya, including the video gallery SCAN which she started as a hub for experimental video art, also inherits the achievements of her father. Ukichiro, under the conviction that science should not solely concentrate on the study of its objects, but must rather study and record the structures of the observational process within which objects appear, organized a network of artists and cultural figures, and further founded the documentary film production organization “Iwanami Eiga,” whose activities and accomplishments in the post-war Japanese cinema can be compared to Neorealism in Italy.

There is no mystery in fogs. The ambiguity lies in the (idea of) object itself that we humans desire to find there. Fog certainly exposes the various ideas (and illusions) that people conceive, along with their uncertainties. That is precisely why we must not drown ourselves in its ambiguity and see fog, and the swinging movement created by the innumerable particles that form fog, with a distinct vision. What we must dispel is our own clouded eyes, deceived by (our own illusions and ideas that we project onto) fog.

What is being emancipated from the tips of the nozzle right now — it is the very energy of nature that dodge past all authority and keep hovering around in a brisk manner; it is free will per se that resists all power. The innumerable water particles are creating a free association.

_

Translated by You Nakai

However if one looks at natural snow with that perspective, one can find similar weird forms. After you discover one irregularity you notice others, one after another, at various stages of development showing that natural snow is also capable of failure to our great relief.

Once I came upon a most marvelous example of failed development in natural snow and cried out, “Come look, they’ve made another mistake!” My assistant Mr. H. peered into the microscope and his face lit up with a blissful smile.

Ukichiro Nakaya, Snow Postscripts